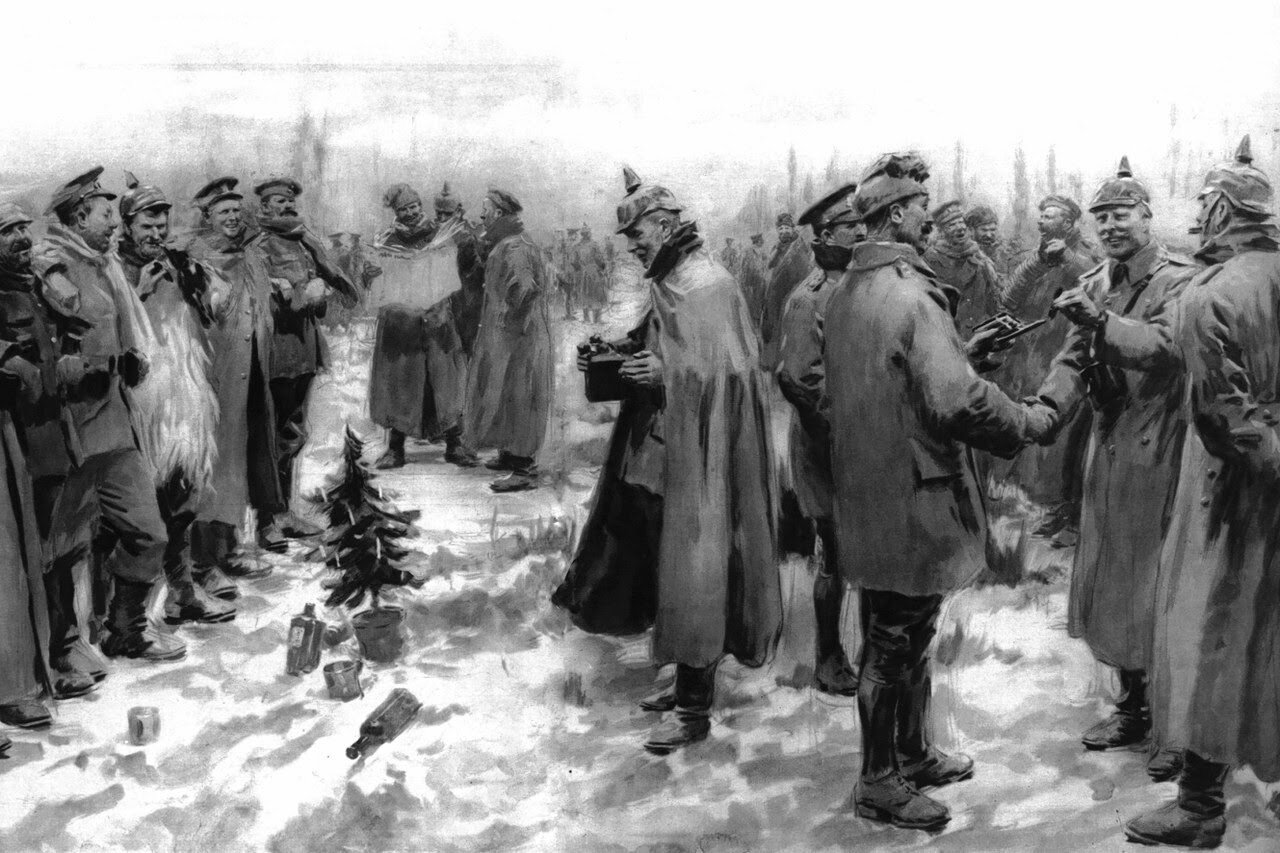

It’s known as The Christmas Truce, and few events in history illustrate that when wars are fought, soldiers on the field don’t feel any real malice toward those they are asked to try to kill. The History Channel proclaimed it to be “one of the most storied and strangest moments of the Great War — or of any war in history.”

It was 1914 when, despite the orders of their commanding officers and leaders, soldiers threw aside their weapons, got out of the trenches and had a make-shift Christmas party with those that just hours before they’d been trying to kill.

Leading up to this impromptu truce in 1914, Pope Benedict XV had asked that the governments participating in the war negotiate a truce for one day, so that “the guns may fall silent at least upon the night the angels sang.” There was also an Open Christmas Letter from British women’s suffragists to the women of Germany and Austria, asking for peace.

A resolution submitted to the U.S. Senate sought to have countries at war cease fighting for 20 days — including Christmas — “with the hope that the cessation of hostilities … may stimulate reflection upon the part of the nations at war as to the meaning and spirit of Christmas time.”

World leaders resisted. But national politics didn’t faze the battleground soldiers. The cessation of fighting and killing stopped abruptly.

One writer observed, “Stuck knee deep in their muddy trenches along lines so close together, the soldiers on both sides, who’d commonly thrown insults back and forth, started adopting a slightly more apathetic view of the war, more of a ‘live and let live’ policy. In some cases, they even started tossing newspapers and other things back and forth, bartering for supplies like cigarettes, rations and the like, and holding conversations across the trenches.”

It was a welcome reprieve from miserable circumstances. One description of the scene noted, “It had been pouring, and mud lay deep in the trenches; they were caked from head to foot, and I have never seen anything like their rifles … they (soldiers) were just lying about the trenches getting stiff and cold. One fellow got both feet jammed in the clay, and when told to get up by an officer, had to get on all fours. He then got his hands stuck too, and was caught like a fly on a flypaper.”

Andrew Todd, identified as a ‘Royal Engineer,’ said, “The trenches are only 60 yards apart at one place, and every morning about breakfast time one of the soldiers sticks a board in the air. As soon as this board goes up all firing ceases, and men from either side draw their water and rations. All through the breakfast hour, and so long as this board is up, silence reigns supreme, but whenever the board comes down, the first unlucky devil who shows even so much as a hand gets a bullet through it.”

Lt. Geoffrey Heinekey told of a situation on Dec. 19 when “a most extraordinary thing happened … Some Germans came out and held up their hands and began to take in some of their wounded and so we ourselves immediately got out of our trenches and began bringing in our wounded also. The Germans then beckoned to us and a lot of us went over and talked to them and they helped us to bury our dead. This lasted the whole morning and I talked to several of them and I must say they seemed extraordinarily fine men … It seems too ironical for words. There, the night before we had been having a terrific battle and the morning after, there we were smoking their cigarettes and they smoking ours.

“This type of behavior, perhaps inherent in any war where the two sides have to live and fight in such close proprieties and for such a long duration, began popping up more and more in sections of the line, prompting the army leaders to issue strict orders forbidding any fraternization with the ‘enemy.’”

Christmas Eve 1914 stands out as one of the most unique times of warfare. It began along the trenches near Ypres, Belgium. German troops set up Christmas trees, sang carols and lit candles. The British and French joined in the singing, and before long soldiers were wishing those from other countries Christmas greetings.

Andrew McGowan, dean of the Berkeley Divinity School at Yale, tells of the British soldier who wrote a letter home and said, “While you were eating your turkey … I was out talking and shaking hands with the very men I had been trying to kill a few hours before! It was astounding!”

Another soldier, Bruce Barinsfather, noted, “I wouldn’t have missed that unique and weird Christmas Day for anything … I spotted a German officer, and being a bit of a collector, I intimated to him that I had taken a fancy to some of his buttons … I brought out my wire clippers and, with a few deft snips, removed a couple of his buttons and put them in my pocket. I then gave him two of mine in exchange … The last I saw was one of my machine gunners, who was a bit of an amateur hairdresser in civil life, cutting the unnaturally long hair of a docile German, who was patiently kneeling on the ground whilst the automatic clippers crept up the back of his neck.”

McGowan quotes a Jan. 1, 1915 article in the South Wales Echo which said: “When the history of the war is written, one of the episodes which chroniclers will seize upon as one of its most surprising features will undoubtedly be the manner in which the foes celebrated Christmas. How they fraternized in each other’s trenches, played soccer, rode races, held sing-songs, and scrupulously adhered to their unofficial truce will certainly go down as one of the greatest surprises of a surprising war.”

The History Channel related what British machine gunner Bruce Bairnsfather wrote in his memoirs.

“Here they were — the actual, practical soldiers of the German army. There was not an atom of hate on either side.”

It wasn’t confined to that one battlefield. Starting on Christmas Eve, small pockets of French, German, Belgian and British troops held impromptu cease-fires across the Western Front, with reports of some on the Eastern Front as well. Some accounts suggest a few of these unofficial truces remained in effect for days.

Other diaries and letters describe scenes of men helping enemy soldiers collect their dead. Of course, there were plenty to collect.

The Christmas Truce was not repeated the following year, nor any year after that, even though there were reports of very isolated, temporary truces in 1915.

To commemorate the 1914 truce, nine people from Britain traveled to Belgium in December 1999. They wore uniforms they made, trying to mimic those worn by soldiers in 1914. They dug trenches and placed sandbags, and for a few days tried to reenact the 1914 event. They ate rations while trying to not sink into the mud. Afterwards, they filled in the trenches and left a wooden cross to mark the spot. People living nearby treated the cross so it would last through the winter, then set it in a concrete base and planted flowers around it, commemorating the time when — against all odds and orders — men from warring nations stopped trying to kill one another, and for a few days, lived at peace.