In the 1920s, an agricultural depression gripped the nation. During those lean economic times, America’s record companies struggled to expand their markets and sales.

They began sending recording crews across the country to set up temporary studios to record regional musicians. This was how the Carter Family was discovered in a recording studio in Bristol, Tennessee. It’s the story of other musicians from across the county, from the blues of Memphis, Chicago jazz, and gospel musicians from across the south.

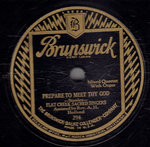

In 1928 the Brunswick Record Company set up a studio in downtown Atlanta. One of the invitations was extended to the Flat Creek Sacred Singers. The quartet was composed of members of the Propes and Bagwell families from Flat Creek Baptist Church in Hall County, Georgia. Flat Creek was a small country church established in 1818, less than two miles from the Cherokee Nation.

It was called, “singing in a can.” For two days they gathered around a single microphone recording 10 songs, two songs per 78 record on a total of five records, which, according to Brunswick’s advertising, were top sellers. One of the company's ads, which may have stretched the truth a bit, stated, “Everyone south of the Mason Dixon line has heard of the Flat Creek Baptist Church and the Flat Creek Sacred Singers.”

Benjamin Propes sang lead, his son James Marlow Propes sang bass, daughter Shelly Propes Mundy sang soprano, James Bagwell was the baritone and James’ daughter Lorina Bagwell Brown played the organ. They sang in simple four-part harmony, which they had learned at singing schools of the shape note tradition. Until the early 1950s the church hosted singing schools in late summer or early fall.

Their pastor Rev. A. H. Holland accompanied them to Atlanta and recorded short sermons on two of the records. Since the running time of each side was about three minutes, the sermons were very short, one minute each. Holland, who at the time was in his 80’s, was a bi-vocational pastor who was a telegraph operator during the week. Born in 1841 he had been wounded and captured at the battle of Gettysburg in 1863. Yet in his ripe old age, he was not afraid to use new technology to preach the word.

They were paid $400 plus royalties for the two days of work. A considerable sum in the 1920s, especially since Georgia was in the midst of a two-year drought on top of the boll weevils' devastating impact on cotton crops. It was money that helped them get through tough times.

The old songs they sang included the themes of hope, heaven, and evangelism, and their playlist included one “mother” song, “Mother Tell Me about the Angels.” Sentimental “mother” songs were popular at the time, and in fact some hymnbooks of the era had more “mother” songs than Christmas carols. It was singing from the heart that was meant to touch hearts and warm the ears of heaven.

The quartet sang across north Georgia, often at revivals and fifth Sunday night sings. They sang at the Atlanta Courthouse where prisoners from the jail were brought to listen and undoubtedly were found wiping away a tear or two from their eyes. For a while, they had a regular spot on a weekly Saturday radio program in Gainesville. Each week, they would stand in a sound studio, “singing in a can,” as people across north Georgia turned their “radio on to listen to the music fill the air, and get in touch with God!”

With the exception of Lorina Bagwell Brown, who married into a church family nearby, they are all buried in the old Flat Creek Baptist Cemetery. The last quartet member died in 1987. They are surrounded by the remains of family members, friends, and a number of Cherokee who were early members of the fellowship. For many years their voices had not been heard, but the old music drifted through the church and across the old sacred grounds one more time in May 2018.

As a part of the church’s bicentennial homecoming celebration, a video was prepared that told the story of the Flat Creek Sacred Singers. It's a story most of the church members had never heard, and it featured one of the 1928 recordings. As the song on the video concluded, some of their descendants, in a transformational moment, gathered on the platform and finished singing the song with those who had gone before, visually and audibly linking the past with the present.

It was a poignant reminder that although they have been gone for many years, their voices still are heard through their descendants and all who join in a spirit of worship. That, “through faith, though he is dead, he still speaks” (Hebrews 11:4b). It was a reminder that songs with themes of hope, heaven, evangelism, and family have no expiration date on this side of eternity.

It also was a reminder that all worship is a mere dress rehearsal for eternity, “When the trumpet of the Lord shall sound, and time shall be no more, and the morning breaks, eternal, bright and fair; when the saved of earth shall gather over on the other shore, and the roll is called up yonder, I'll be there.”

__

Charles Jones is a newspaper columnist, Baptist historian, and retired pastor.